Using Git and the Eclipse IDE, you have a series of commits in your branch history, but need to back up to an earlier version. The Git Reset feature is a powerful tool with just a whiff of danger, and is accessible with just a couple clicks in Eclipse.

In Eclipse, switch to the History view. In my example it shows a series of 3 changes, 3 separate committed versions of the Person file. After commit 6d5ef3e, the HEAD (shown), Index, and Working Directory all have the same version, Person 3.0.

Right-click on any of the commits to show the context menu,

and select Reset to show a sub-menu with 3 options: Soft, Mixed and Hard. These options affect

which of git's 3 sets of files are Reset.

The different shades of Reset affect one, two or all three of these sets.

So, in the History view above, everything is updated to version 3 of the Person file. How can we use Eclipse and Git to back up to Person version 2? Right-click on the version 2 commit and choose Reset.

A Hard Reset changes the file version in each of the three Git file sets: HEAD, Index and Working Directory. This effectively throws out an entire commit. It disappears from the History, and version 3 is replaced with version 2 in both the Index and the Working Directory as well. Since Eclipse EGit is about to change the Working Directory, it asks, “Are you sure?”

In Eclipse, switch to the History view. In my example it shows a series of 3 changes, 3 separate committed versions of the Person file. After commit 6d5ef3e, the HEAD (shown), Index, and Working Directory all have the same version, Person 3.0.

Before proceeding, a brief reminder that Git has 3

different sets of the files.

First is the HEAD,

which is everything that is safely committed into the Git repository.

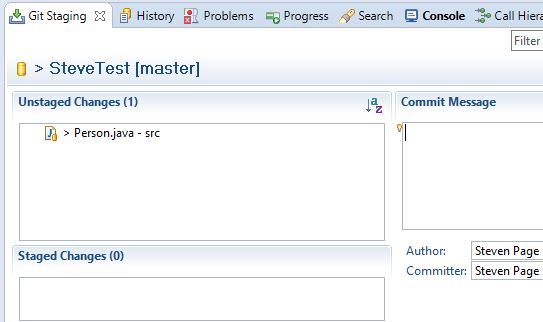

Second is the Index,

which are the files as they will look in the HEAD once you do the next commit - in Eclipse, the Git Staging view's “Staging Area” shows the files ready but not yet committed.

Third is the Working Directory.

Think of this as the Sandbox in which you can work and actually make changes

(the HEAD and Index are not editable files in the same way, they are stored in Git’s

internal representation, not directly accessible for editing purposes).

The different shades of Reset affect one, two or all three of these sets.

So, in the History view above, everything is updated to version 3 of the Person file. How can we use Eclipse and Git to back up to Person version 2? Right-click on the version 2 commit and choose Reset.

Select “Soft (HEAD

Only)” to revert to version 2 only in the HEAD file set. This leaves the

Index and the Working Directory still on version 3. As a result, the History

view changes to reflect the fact that the HEAD now points to Person version 2:

And, since the Index and Working Directory still have

version 3, the Git Staging view shows that version in the Staged Changes, ready

to work on some more in the Working Directory, or commit again.

A Mixed Reset

affects both the HEAD and the Index versions of the file. Selecting this option

alters the History view the same as the Soft Reset above, with the version 3

commit reverted and therefore disappearing. Since the HEAD and Index now have version

2 again, but the Working Directory was not affected by this reset, the file now

reappears in the Git Staging view’s “Unstaged Changes” area.

Selecting Yes will lose all changes that were made in

version 3. They will be gone from the HEAD, the Index and the Working

Directory.

The Hard Reset is the only time when Reset is dangerous. It is a

powerful tool, but use with caution! The other scenarios above can be undone

easily enough. But a Hard Reset overwrites the changes (almost) everywhere.